(Podcast Notes)

Every diver feels afraid at some point.

Uncomfortable as it is during a dive, fear is an unavoidable part of life. In fact, a little fear can help you stay safe and avoid danger. But on a dive fear can be so intense or trouble you so often that it leads to serious problems or at least takes away from the dive.

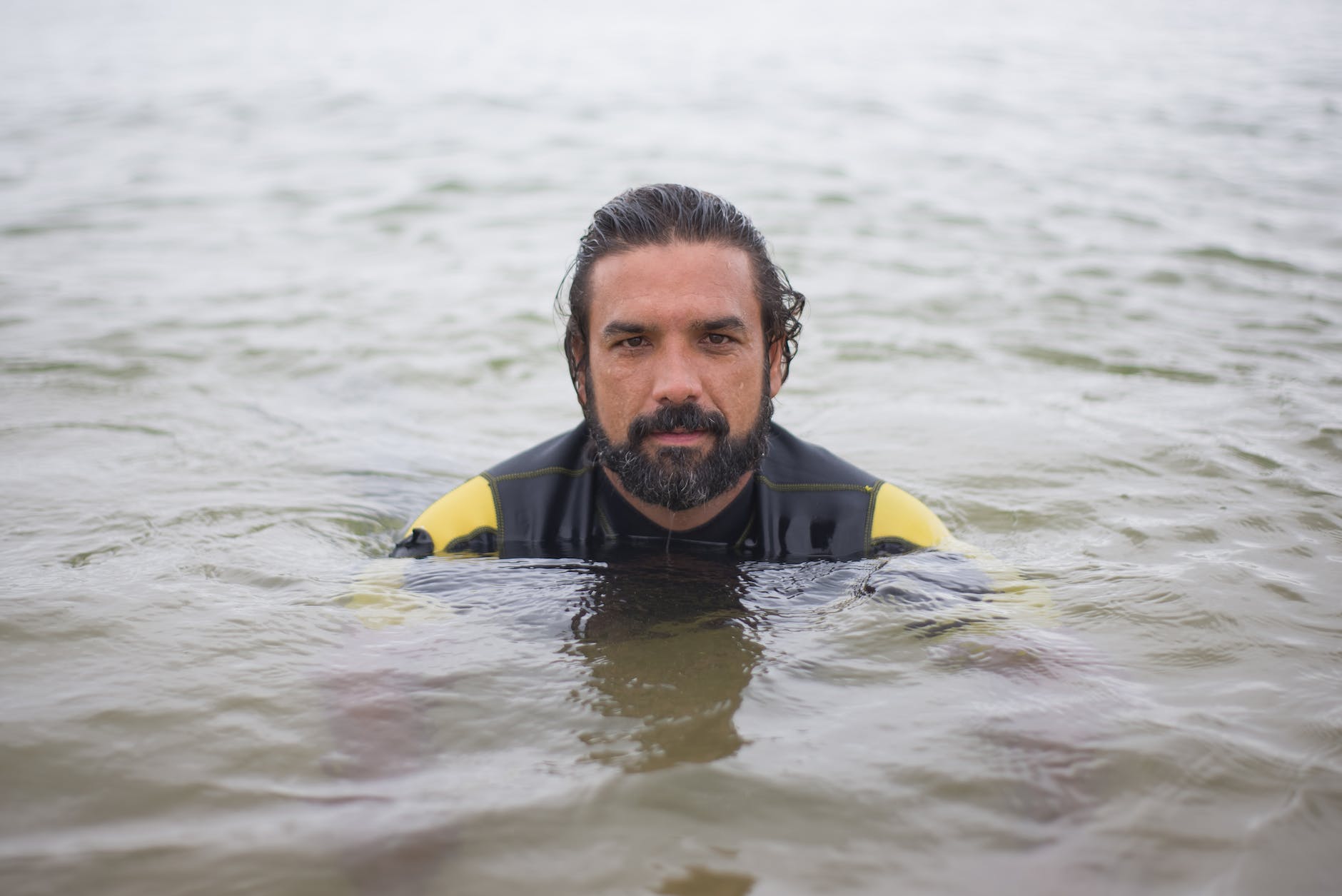

In this post I get allot more detailed than I have in the past but will introduce you a particularly effective methods I use with my clients and many times lead them into situations they fear. Like everything I do on this blog, podcast, and in my dive coaching practice, it has relatable lessons to transfer to daily life outside the aquatic world.

I’m going to discuss:

- What fear is and a few examples

- How fear gets ‘stuck’ and becomes a problem or worse something that can cause a diver to panic

- How I use exposure with coaching clients in the dive environment and how going on guided dives help to overcome their fears and get joy out of the dive.

We experience all sorts of emotions every day. The feelings we have are important because they tell us useful things and prompt us to act in certain ways:

Happiness tells us that something is good, encouraging us to keep doing whatever we’re doing. That reef with the same friendly boxfish that comes up to see you, the post dive celebrations with fellow aquanauts,

You find trash in your favorite area, soda bottles, used condoms, diapers, etc that emotion is disgust. Disgust tells us that something could be toxic, prompting us to avoid or get rid of it. It could be objects or maybe divers or even if at Quinns or another community pond that has vagrants that could be dangerous. Maybe your dive buddy is part of a toxic relationship.

Crash into coral, illegally shoot a gamefish with your spear gun, use plastic bags when you have been telling others how bad you believe they are for the environment, and you violate your own standards? Maybe you purposely didn’t answer a call to meet up with a dive buddy or ditched them on a dive. Guilt tells us that we believe we have done something wrong and encourages us to make amends and repair the damage.

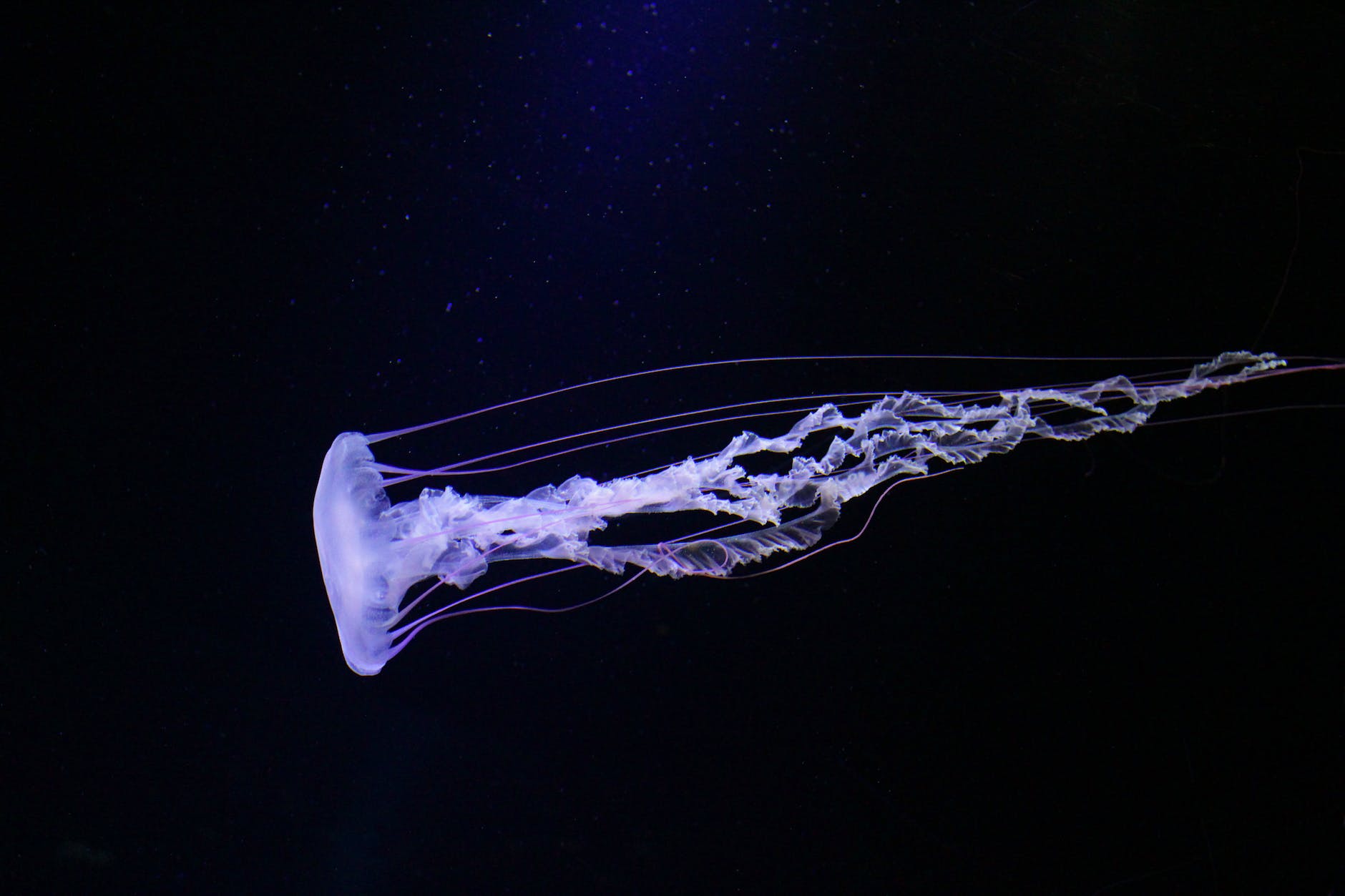

In the same way fear warns us that something might be dangerous. Maybe it’s a certain depth, perhaps diving in the dark or low visibility, or even diving a lake that had a drowning the week before. This prompts us to be cautious, neutralize the threat, or get away from it.

I was diving in Hawaii off of Black Rock in Maui. I was hanging with a ton of Amber Jacks. I was still enough and in that Zen moment that they felt comfortable just letting me drift with them. All of the sudden another massive school of Jacks came darting to the school I was hanging with and in a moment everything dispersed. My immediate fear was a shark was racing in. I remember I got into a fighting stance, pulled my dive knife like I was going to go full on underwater combat mode. Instead of Jaws showing up, It was three huge Tuna on the hunt. We starred each other down the next few moments.

Fear is part of an automatic ‘fight-flight-freeze’ response that most animals including frog people (us divers) experience when they feel they are in danger. Suppose you found yourself in a threatening situation, like crossing paths with a shark. Fear is part of your ‘programming’ that helps you prepare to take one of the following actions:

- Attack the Shark (or my case all three Tune) in self-defense (fight)

- Swim away from the threat or bolt to the surface (flight)

- Stay still, so the Shark (or Tuna) doesn’t think you are a threat (freeze)

When does fear become a problem?

A beeping alarm on your dive computer can help warn you if you ascend too fast, but what if the alarm keeps going off at the wrong time, like when you’ve forgotten to change the battery and the beeping is warning of a failing battery?

Fear becomes a problem when it is too extreme or too frequent. When your fear response is too easily triggered or triggered in the wrong situations, it can lead to serious problems with your mood, relationships, and day-to-day life.

I shared in the blog awhile back about my own startle response. In the blog I wrote getting startled is not the same as being afraid or having fear. It’s part of the survival reflex that has been built and reinforced. In the neural pathway. When a diver (or in the land-based world a non-diver) gets startled, they feel a number of things. There is the adrenalin surge, the mouth dries because of the increase of blood sugar, and the heart rate increases. In my own case I know I breathe faster and talking to others the can produce perspiration, increase muscle tension and they feel “keyed up” or hyper vigilant. This is classic startle response. When someone jumps out from behind cover and grabs you or yells, “HEY!” that may initiate a startle response.

While not the intent of this post, there are some different kinds of fear we should be aware of and I will mot likely cover in another post.

Phobias: Extreme fear that arises in specific situations (e.g., enclosed spaces), or in response to particular things (e.g., masks, underwater, caves, etc).

Panic attacks and panic disorder

Fear that arises in response to certain bodily sensations (e.g., cold, heat, feeling dizzy or short of breath).

Social anxiety: Fears that arise in social settings, providing a demonstration on a skill, testing and performance situations (e.g., Open Water cert, Dive Master presentation, SIT at the PIT).

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD): Fears related to intrusive thoughts or images (e.g., unwanted, repetitive thoughts about harming others).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): Worries that chain together and escalate

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Fears related to a traumatic event

Although people use the words interchangeably there are differences between fear and anxiety:

Fear is about imminent danger where the threat is nearby and specific (e.g. feeling scared when an diving zero visibility)

Anxiety is a more general type of fear – often a feeling of apprehension about threats that might happen in the future (e.g. feeling anxious when worrying “What if the dive boat sinks?”)

We are going to focus on fears since anxieties should be diagnosed by a professional counsellor and I am a professional coach.

So let’s explore fearful body sensations

When you feel afraid, your body reacts in a particular way. Some of the physical sensations that accompany fear while diving include:

Your heart rate and breathing speed up (this gets more oxygen to your muscles, so you’re ready to run or fight).

Your mouth goes dry and your stomach feels uncomfortable before entering the water and breathing the dry air from your regulator.

You might feel lightheaded or dizzy (this is because there is more oxygen in your bloodstream, which will also help you run or fight).

Body changes like these can be useful in a genuinely life-threatening situation, but they can also feel very uncomfortable if the situation isn’t dangerous.

We can also conjure up fearful thoughts and images

Our minds are constantly interpreting the world around us. When we think we’re in danger, our thoughts become focused on potential threats and ways that we can protect ourselves. Like bodily reactions, these responses are quick and automatic. Unfortunately, our brains like to take ‘shortcuts’ if they think danger is present, and they usually have a ‘better-safe-than-sorry’ approach. If you struggle with fear, your thoughts probably tell you that the situation is much more dangerous than it really is. Some of the ways your thoughts can become ‘distorted’ when you feel afraid include:

Catastrophizing: Seeing a situation as much worse than it really is.

Fortune-telling: Predicting that something bad is going to happen

Magnifying and minimizing: Exaggerating how bad things will be- and then feeling like you can’t deal with them.

Dive site chat about Fearful Behaviors

Emotions can prompt you to act, and this is especially true for fear. Two behaviors play a particularly important role in fear – Avoidance and Safety Behaviors. Let’s look at how these work for two divers I coached who were struggling with extreme fear.

Stacy

Sam

Dive site chat about Avoidance

Stacy

Sam

Dive site chat about Safety Behaviors

What do you do when you can’t avoid something that scares you? Safety behaviors are strategies to cope with frightening situations

Stacy

Sam

- Safety behaviors can help you tolerate fearful situations, but they often keep fear going too. This is because:

- Safety behaviors prevent you from learning about what happens if you don’t use them.

- Relying on safety behaviors undermines your belief in your ability to cope.

- If you can’t use a safety behavior for some reason, your fear increases.

Let’s see how our divers could be further impacted:

Stacy

Sam

Breaking the Cycle Through Experience and Exposure

Exposure involves facing the thing that scares you in a planned way for a prolonged period. When you do this repeatedly, your fear starts to decline.

Exposure is effective for two reasons:

When you face your fears and stay in the uncomfortable situation, your body and mind get used to the thing that rattle you. Your fear minimizes because you are used to it in the environment. It’s a bit like diving in a cold body of water. As the water creeps into your wetsuit it feels uncomfortable at first, but you soon get used to it, and eventually stop noticing the temperature.

Confronting what you are afraid of instead of avoiding them allows you to find out how dangerous they really are (or aren’t) and changes to your fearful thoughts. This can lead to helpful changes in the way you think about things that frighten you.

What are the principles of exposure? To be most effective exposure should be:

- Rated and graded. Exposure begins with an uncomfortable activity that feels challenging but not overwhelming. When that activity no longer feels fearful then it’s time to move on to the next situation. Mask clearing is a basic skill that many new divers struggle with. Once its accomplished, its time to move to the next skill that may rattle them

- Prolonged. Your fear will rise when you first expose yourself. Your body is reacting to something that is unnatural, you are underwater many times and this isn’t natural but the fear is. Anything that threatening can invoke the fight-flight-freeze response which is why many divers bolt for the surface instead of working through the issue and safely resolving underwater. I’ve had divers want quit at some point after bolting to the surface. Given an opportunity exposure works when they stay in the situation until their body habituates through guided practice.

- Repeated. If I have a client that struggles with a skill, then we do it over and over until it becomes natural, and the fear subsides. Facing their fear repeatedly helps them get used to it and drives home that they really are safe.

- Without distraction. I often separate spouses, parent-children, and other relationships when working with someone on a skill that brings about fear or diving an area that makes them uncomfortable. I also try to keep distractions to a minimum. Exposure is most effective when you directly face the thing that scares you. This means trying not to use your safety behaviors. A few years ago, I had someone who hated night dives but could eventually get through a few of them when they dove with their boyfriend in specific bodies of water. By taking away the boyfriend as the comfort on the dive, I was able to increase exposure by starting the dives earlier in the evening and finishing at dark. I gradually moved the dive start and stop time to a point she was doing night dives with me just tagging along.

As a coach I seek to help my client understand exposure a little better and use that understanding to overcome their fears. In practice we work on three distinct areas:

- Identifying the fear and prepare for exposure

- Doing exposure with the diver

- Keeping the diver’s fears at bay

One of the things I use with my clients is a Fear Ladder. Not going to discuss that at this point, but if interested contact me so we can work on this together.

With my clients I take them through 6 steps of exposure in several sessions

Choose a situation on the Fear Ladder.

- The highest that you’re willing to face – and set aside a dive for your exposure session.

- We dive the first exposure. When my diver is ready to expose themselves to the situation that scares them or produces fear.

- On a dive slate during and after the dive I have them rate their fear level as they start the exposure on a scale of 1 to 10 and continue through the dive

- Include notes about what they are feeing fearful of and show me

- We stop either when the fear has dropped to a point they become slightly at ease. I let them decide based on the fear level and guide how long the exposure exercise lasts.

- It’s important to journal the experience. At the end of the exposure, together we process the experience and I have them write their fear level in their Dive Journal. Along with this to think, reflect, and record the experience.

- High 5 Time! It’s time to celebrate the progress

- BREATHE!!! It’s now an opportunity to relax. What did you learn during your exposure session? When you get to the end of the session, use your record to reflect on what you learned. For example, did your worst fear come true? If it didn’t, what does that tell you about the thing that scares you?

Now what?

Since repetition is one of the most important parts of exposure, we schedule additional sessions. Most of my clients will follow this up with success dives either the same day or over a series of days. Sometimes after an exposure I give them play time where we can go and just enjoy the dive. Its best to have 3-5 exposure sessions for each specific fear. I had a client a few years ago didn’t like descending an anchor line or from my dive float. We spent several sessions diving from the shore to the float underwater and then coming up the dive float. We did this several sessions over two days with the total of six dives. On the following weekend we did all our dives from the dive float down to the skills platform.

I also take my clients to different areas for exposure sessions in different settings. For my diver with the fear of having anything looming overhead, I used a large concreate tube in the lake and we did multiple swim throughs. I then built a PVC frame and zip-tied a tarp around the sides and over the top and we played in the training pool as well as a small pond doing swim throughs and then tic-tac-toe as well as other games inside the mockup. Exposure works best when it takes place in different settings, so you learn that you are safe in every possible context. We even did night dives since holding sessions at different times, in different places, and with different people helps to reinforce the newfound courage.

Beating fears under regular guided exposure will help you in overcoming your fears and enjoying more dives. Lately I’ve even found a few methods where I can coach virtually with clients I can’t be there to dive with.

Through this method together we make facing your fears a part of your lifestyle, or a habit. Whenever an opportunity arises to face a fear, take it. Every time you step outside of your comfort zone, you leave less room for fear.

Leave a comment